Not just Alzheimer’s: Caregiver finds support for frontotemporal dementia

Diana Hayden of Aptos is on a mission to help families learn about Alzheimer’s Association support services for those facing dementias other than Alzheimer’s. A friend told Diana about the Alzheimer’s Association after her husband, Chris, was diagnosed with frontotemporal degeneration, also known as frontotemporal dementia (FTD).

Many don’t know that the Alzheimer’s Association was founded in 1980 as the “Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association.” While the majority of dementia cases are caused by Alzheimer’s disease, there are many other conditions that cause dementia.

The Alzheimer’s Association supports families impacted by any form of dementia and related cognitive conditions.

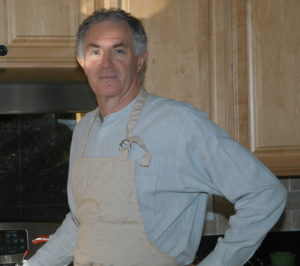

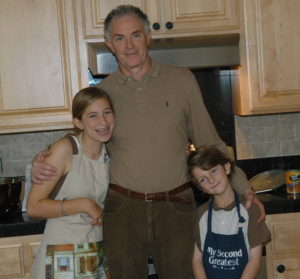

Chris the entertainer

Chris Hayden had always been a very energetic and outgoing person. He was a great chef who loved to invite friends over for dinner.

When Chris was in his mid-fifties, Diana started noticing changes in his personality and behavior. He backed away from things he would normally enjoy, such as cooking, entertaining and playing with his grandchildren.

Diana and Chris had always enjoyed talking with each other while taking long walks. Chris stopped talking during their walks.

A long and winding path to a diagnosis

Getting a diagnosis can be challenging, especially for those who are younger and/or have a form of dementia other than Alzheimer’s. This was very true for Chris.

Initially, Chris’ doctor diagnosed him with depression, as part of a “midlife crisis.” Chris saw a psychologist and a psychiatrist. He and Diana went for marriage counseling.

During this time, Chris withdrew even more. Diana knew that something wasn’t right. She continued to share her concerns with Chris’ health care providers.

In August 2009, Chris’ doctor ordered an MRI. He told Chris and Diana that the results were normal.

Chris’ psychiatrist recommended a neuropsychological exam, which Chris completed in January 2010. Chris scored high on most of the tests, but there were certain areas where he scored extremely low.

One area was facial expression recognition. Chris was not able to accurately interpret the emotions of others. This was a red flag for Diana.

In May of 2010, Chris’ physician finally referred Chris to a neurologist. The neurologist had experience with frontotemporal dementia and quickly recognized Chris’ symptoms.

On Chris’ previous MRI, the neurologist noted indicators of neurodegeneration. He promptly referred Chris to the UC San Francisco Memory and Aging Center.

After more testing and examination at UC San Francisco, Chris was diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia in July 2010. He was almost 61 years old.

Accommodations at work

Chris was still working when he received his diagnosis. An engineer by training, Chris had been working as a financial analyst and appraiser in the semiconductor industry for almost 10 years.

While Chris was going through the diagnostic process, he and Diana spoke with his supervisor. Chris was still able to do the technical part of his job.

In meetings, it was difficult for Chris to talk and express his thoughts concisely. Chris’ boss offered to provide questions in advance of meetings, so that Chris could prepare written responses. This allowed Chris to remain in his job after he received the FTD diagnosis.

A series of health challenges

In November 2010, Chris had the first of several health challenges that seemed to exacerbate the progression of his FTD. He slipped and fell while on a business trip. He tore both quadriceps and had to have surgery.

In January 2011, Chris was in the hospital again for prostate surgery, followed by hernia surgery in February. The surgeries and hospitalizations caused setbacks and worsened Chris’ dementia symptoms. He went on disability and wasn’t able to return to work.

When Chris’ disability coverage ended, his employer terminated his employment. Unfortunately, this was six months before Chris would have been with the company for 10 years. After 10 years of employment, he would have been eligible for lifetime disability and health insurance coverage.

Diana reached out to Chris’ employer, asking if Chris could use his vacation leave to help him reach 10 years of employment. They denied her request.

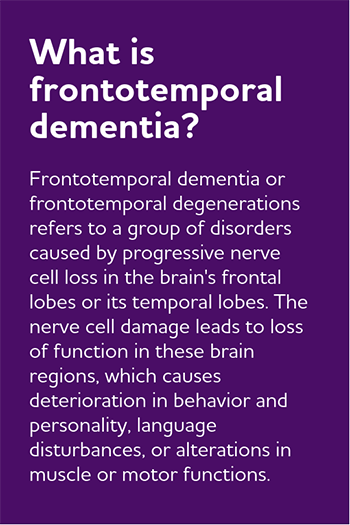

Understanding FTD symptoms

Some FTD symptoms can be very different from those of Alzheimer’s disease. The symptoms also vary depending on which type, or variant, of FTD the person has. Changes in personality, speaking and/or motor function may be predominant.

Most of Chris’ symptoms were behavioral. He had mood changes and often engaged in socially inappropriate behaviors.

Chris’s behavior was unpredictable. Chris:

- Often acted withdrawn or aggressive.

- Would talk to strangers on the street or in restaurants, sometimes sitting down at their table.

- Exhibited obsessive or compulsive behaviors: Chris would go to the store to buy one shirt and come home with 10.

- Ate more sweets, which he had rarely eaten in the past.

- Told jokes that were inappropriate for the setting.

- Fell for scams, such as clicking on ads and giving personal information online to apply for mortgages or credit cards that he didn’t need.

- Sometimes resisted showering and other times did not want to get out of the shower.

As the disease progressed, Chris started to have more difficulty with reading comprehension and with speaking. He would easily lose focus.

In the beginning, Diana would catch herself thinking that Chris was trying to be mean or difficult. As she learned more about FTD, her understanding of the disease grew, and she recognized his behaviors as symptoms of the disease.

A lonely journey

Most of Chris’ family lived on the east coast. When Chris first developed FTD, his father was experiencing his own physical health issues. Six months later, one of Chris’ brothers was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). The family focused on their ill loved ones on the east coast.

Diana’s children lived nearby and provided emotional support, but they were busy with their careers and families. Chris’ personality and behavioral changes also tended to keep friends from visiting. They had difficulty with Chris’ inability to speak and connect with them.

Chris and Diana were living in the Santa Cruz mountains. Chris kept getting lost on the property and Diana knew that they had to move.

A recommendation from a friend

In 2011, Chris fell again and was readmitted to the hospital. When Chris left the hospital, Diana moved him into a residential care community.

Shortly afterwards, a friend told Diana about a caregiver support group offered by the Alzheimer’s Association. Diana started attending the group.

At the group, Diana heard from people at different places in their caregiving journeys. Other caregivers shared what they had encountered and what they learned.

Through the Alzheimer’s Association, Diana learned about other community resources, such as elder care attorneys, caregiver resource centers and the long-term care ombudsman.

She attended the annual Santa Cruz education conference and the Walk to End Alzheimer’s.

Participating in research

Diana and Chris stayed involved with the UC San Francisco Memory and Aging Center as well. They enrolled in a research study. Diana attended an education group for caregivers.

She found participating in the research study to be rewarding and helpful. The research team were very responsive and answered Diana’s questions about the disease. Even after Chris could no longer go to UC San Francisco for the research study appointments, his doctors stayed in touch with the family.

A difficult journey, emotionally and financially

Despite the support Diana received through the Alzheimer’s Association and the Memory and Aging Center, is was an extremely difficult journey.

Chris’ younger age, behavioral symptoms and physical size made caregiving difficult. Diana found that most residential care facilities were reluctant to take a resident who was young, strong and sometimes aggressive. Many staff were not well-trained to manage Chris’ FTD symptoms.

Three different facilities evicted Chris. Diana was constantly trying to make sure that he had the appropriate care and that staff could manage his behaviors.

Chris lived in care facilities for over seven years. Diana spent a large part of their retirement savings on his care.

Falls, infections and other health issues led to frequent hospitalizations. Diana remembers being constantly on edge, just waiting to get a call about another issue with Chris.

Missing his feedback

Caring for Chris was extremely stressful and overwhelming for Diana. She often second guessed herself. “Am I doing enough,” Diana would ask herself. “How much longer can I go on with this?”

Chris’ change in personality was also difficult. As the disease progressed, Chris became very apathetic.

Chris wouldn’t respond verbally or nonverbally. He didn’t talk for the last four years of his life.

Diana often interacted with other residents when she visited Chris. Sometimes she would take in baked goods for Chris and others.

It was extremely difficult for Diana to not receive any feedback on whether Chris approved of the actions she was taking. She appreciated the positive responses she received from other individuals. She also appreciated the invaluable support of the caregivers.

Diana admits that she neglected her own health during this time. She found the Alzheimer’s Association support group to be helpful. She also walked frequently and practiced yoga.

Chris died in February 2018. In looking back on her journey, Diana is glad that she was able to be there for Chris. She shared, “I can’t imagine how it would be if someone didn’t have an advocate and someone to love and care for them.”

A new role: Advocacy volunteer

Recently, Diana has started to volunteer for the Alzheimer’s Association as an advocate. In this role, she shares her story with state and federal legislators and encourages them to take action.

She has learned that people often don’t understand how difficult it is to get support and help with care. While she was caring for Chris, many people mistakenly thought that Medicare was covering the cost of Chris’ long-term care.

Diana and other Alzheimer’s Impact Movement advocates are encouraging Congress to pass the Building Our Largest Dementia (BOLD) Infrastructure for Alzheimer’s Act (S. 2076/H.R. 4256). The bill would create an Alzheimer’s public health infrastructure across the country to implement effective Alzheimer’s interventions focused on issues such as increasing early detection and diagnosis, reducing risk and preventing avoidable hospitalizations. Diana believes that legislation such as the BOLD Alzheimer’s Act has the potential to help other families receive an accurate diagnosis and be connected to community resources more quickly.

Diana’s Congressional Representative, Jimmy Panetta, has co-sponsored the BOLD Act and also supported greater federal dementia research funding. Federal funding for FTD research has risen from $37M in fiscal year 2014 to an estimated $96M in fiscal year 2018. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is currently supporting three large FTD research projects, including one at UC San Francisco.

Helping others

Diana is very thankful that others connected her with the Alzheimer’s Association and the UC San Francisco Memory and Aging Center. The day-to-day support, education and resources helped her understand the disease and be a better caregiver. Staff and volunteers also understood the different needs of those who had a younger-onset diagnosis (i.e., diagnosed before age 65).

Diana often felt alone when going through her caregiving journey. “Another reason I’m interested in advocacy is just to publicize more that the Alzheimer’s Association provides support related to other dementias” said Diana. “I would have never found them if it hadn’t been for my friend.”

Learn more: