Neurodiverse husband adapts to care for wife with dementia

By Alan Freedman

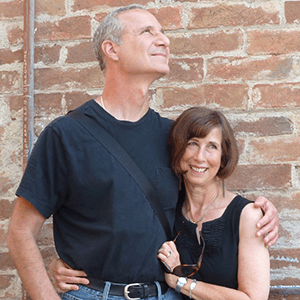

Before Alzheimer’s disease, Robyn had been a natural communicator, a leader, and someone who understood people instinctively. Her husband, Alan, is introverted and autistic. In his own words, Alan shares how their roles reversed as her illness progressed, and how he learned to read rooms, notice feelings, and find unconventional tools to provide care.

Oil and water, logic and heart

Robyn built her career in communications, serving as Chief Communications Officer for the San Francisco Health Plan and later as Public Information Officer for the San Mateo County Department of Health. She was the definition of a people person: intuitive, extroverted, and deeply connected to people.

I was her opposite. Neurodiverse and introverted, I built my career in data and software—fields where logic mattered more than emotional connection. For years, our differences balanced each other. But in 2018, I noticed the first signs of dementia in Robyn, and the balance started to shift.

Noting the changes

As she misplaced words, forgot details, and sometimes struggled with directions, my neurodiverse brain tallied each instance like a cash register: factually, precisely, and without sentiment. Despite my very rational case for early intervention, Robyn hesitated to tell our doctor she was experiencing cognitive issues until 2020. It took until 2023 before she accepted the neurologist’s diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease.

As the disease progressed, I realized my standard way of handling things—counting, analyzing, and reporting—fell short in this new reality. I had to adapt to her quirks and peculiarities the way she had always adapted to mine.

When neurodiversity meets dementia

Being neurodiverse has strengths and blind spots. One strength is that I can observe and analyze without being swept up by emotion—a skill that later helped me see the patterns in Robyn’s illness.

A blind spot is that I often can’t understand why someone feels the way they do, and my instinct is to answer every question with blunt truth. I’m also introverted, so small talk and sharing my own feelings have never been easy. That makes it feel unnatural to act as Robyn’s constant companion or ask people for support. Yet, as is often the case, my traits push me to find new ways to connect and cope.

Reaching out

Fortunately, a friend recommended the Savvy Caregiver program from The Alzheimer’s Association. This six-week course was conducted online, which made it feel safe for an introvert.

In the very first session, I learned to step back from my instinct to take words at face value and instead look for the feeling underneath. That shift didn’t come naturally, but it’s made me a better partner in her care.

My instinct to always tell the truth was also not helping. Through the informal conversations that took place during the class sessions, I came to see that small fibs aren’t lies—they’re mercies. They keep Robyn safe, calm, and connected. That understanding gave me permission to set aside my rigid need for accuracy and focus instead on kindness.

Translating human behaviors

Caring for Robyn has taught me that her Alzheimer’s changes how she expresses needs, and sometimes those needs aren’t easy for me to interpret. Fortunately, I developed a trick long ago. Because I’ve always related to animals more easily than people, I translate human behavior into animal terms.

Sometimes Robyn verbalizes every thought that passes through her head, or comments on each and every bite of food. In those moments, I picture a songbird, singing steadily to stay connected.

She has also become extremely picky about food. At mealtime, she reminds me of a cat: selective, stubborn, and adamant about what she doesn’t want.

And when she needs constant reassurance, I see a golden retriever with big, pleading eyes. Imagining Robyn as a songbird, a cat, or a retriever takes away judgment and helps me focus on what she needs in that moment.

Companions don’t need to be human

Of course, sometimes the best animal stand-in isn’t imaginary—it’s real, with fur and paws.

Robyn likes to talk in a stream-of-consciousness style, saying her thoughts out loud as they come. I, on the other hand, use communication to share information. I couldn’t sit beside her all day as a passive listener. But when I stepped away, she felt lonely.

To help with this, we went to a local rescue and adopted Jake, a cream-colored cat with big blue eyes and a gift for loyalty. He quickly became her shadow.

Jake sleeps beside her, follows her from room to room, and even waits outside her bathroom door. I often overhear Robyn chatting comfortably with him, and his instinctive devotion speaks louder than words. Sometimes, companionship purrs.

Finding the right words

Some topics, like bringing in outside caregiver help, upset Robyn. Others, like wondering where Jake has gone, trigger anxiety. While The Savvy Caregiver program helped me set aside my rigid need for accuracy, I still struggled to come up with the right gentle words in the moment.

That’s when I turned to another kind of non-human helper—artificial intelligence. I used ChatGPT to suggest non-threatening introductions and small reassurances that don’t come naturally to me.

It comforts Robyn if I tell her, “I just saw Jake curled up in the sunny spot by the window,” or, “He’s keeping watch by the front door—I walked past him a minute ago,” even when I haven’t seen him in hours.

Technology gives me words when mine fall short and helps me replace sharp truths with softer reassurances.

Reversing roles

In the early years of our marriage, I was the socially awkward one and Robyn was the natural communicator. Now dementia is making conversation difficult for her, and even sound above a whisper feels too much. She shies from touch and avoids foods she once enjoyed. It’s as if she’s drifted into my world.

In response, I’ve become more like her. I explain things to waiters, schedule appointments, and even scan for things that may upset her. I gently steer her away from the well-meaning friend who helps too much, the conversation that’s too loud or too fast, or even a chair that squeaks.

Alzheimer’s requires a slower rhythm, and my autistic brain has a hard time matching other people’s pace. The Savvy Caregiver program taught me to break down tasks and patiently guide Robyn through each step. That lesson hasn’t just applied to caregiving—it’s helped me develop some of Robyn’s people skills, softening edges I thought were unchangeable.

In short: I’ve become the one supporting neurodiversity, and it’s helping me grow in ways I once thought were beyond me.

Finding connection in new ways

Our journey has taught me that love adapts. In our house, that means it may lean on artificial intelligence, a loyal cat, casting people as animals, or even a burgeoning ability to read rooms.

The Savvy Caregiver course also showed me how powerful it can be to learn alongside others walking the same road. For someone introverted and autistic, that sense of community was unexpected—and a reminder that connection doesn’t stop at our doorstep.

For more information on caregiving visit alz.org/caregiving. Learn what to expect, where to find support and how best to care for your loved one living with the disease.

For more information on the next Savvy Caregiver course, visit alz.org/crf.