Finding ways to connect to friends living with dementia

by Pat Butler

Today’s guest writer shares the story of her mother who was living with Alzheimer’s disease. Because it was the 1980s information on the disease was limited. Pat and her family did their best to care for their mother and help get her the support she needed. Over 30 years later, Pat finds that some of her friends are experiencing cognitive decline. She shares her tips on how she continues to show up for her friends.

During snowy winters, the drive from our Ottawa home to visit my parents in Beaconsfield, Quebec could be treacherous. So, in 1980 we postponed the trek until late March. Mum, 74, came to the side door of the house to greet me and I will never forget the shocking change in her eyes appearance. Her gaze was noticeably vacant, and her pupils seemed smaller than usual.

Since the previous November, when she had contracted shingles, her conversation over the phone had been vague and imprecise. In person it was even more unsettling. As the 34-year-old mother of two little boys, I was preoccupied with our hectic lives in Ottawa: completing a master’s in education, preparing to sell our house, and packing up to move to England two months later. I had no idea how to relate to my disappearing mother.

Hale and hearty 79-year-old Dad insisted that she was “just a little forgetful.” Because I believed her mental confusion was caused by the shingles pain, I wasn’t concerned that her condition was irreversible. She’ll soon return to normal, I thought. Once the pain stops.

It only got worse.

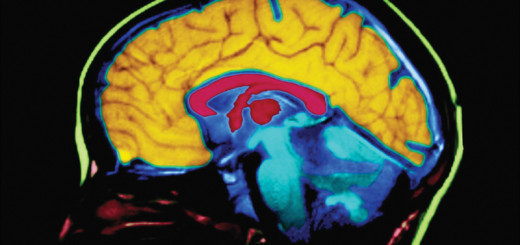

Six years later, Mum was placed in a long term care setting for people living with dementia. After six more years in long term care, she died at 86. An autopsy revealed that she had Alzheimer’s disease. Today, doctors use several tests like Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) to diagnose Alzheimer’s, and other forms of dementia, while patients are still alive.

Watching my beautiful, talented, loving mother deteriorate over 12 long years was absolute hell. When reliving my helplessness, I picture Mum sitting in a canoe without a paddle – drifting away from me toward a river’s rapids. I’d never seen cognitive decline up close and was unable to convince Dad to hire help. His stubborn denial that she needed outside care made everything worse. A broken kneecap eventually put Mum in the hospital, which led to the first of two care settings.

Fast forward 30 plus years. Today my husband and I know four people around our age who are drifting away from our long-term friendships – thanks to dementia. Some have mild cognitive impairment; others have announced their own Alzheimer’s diagnosis. Realistically, their numbers will grow with each passing year, so I want to capture ways to interact with loved ones who are still alive physically but experiencing cognitive decline. It would be easy to just ignore them, but both the person living with the disease and their families deserve your making the effort to reach out.

All our affected friends have lost the ability to correspond by email and talk on the telephone. The act of removing their contact information from our computers is both depressing and final.

Rather than give up and abandon these people, I endeavor to meet each person exactly where they are today. This takes forethought, an opportunity to meet in person, and being present. It takes courage to just let go of old topics and shared experiences, but doing so is like applying a soothing cream to rough skin. Everything feels better.

I list some principles which have for me worked so far:

1. Honour the person’s emotions.

The last time I interacted with Mum when she lived at home, I learned an important lesson. When visiting with my sons of 11 and 14, I’d taken over all meal preparation and household organization. After a few days Dad took me aside and explained Mum was feeling hurt.

“You’ve taken over all her tasks and hardly ever speak to her,” he said. “I’ve been told that a [person living with the disease’s] emotions are the last thing to go, so they can still feel ignored and offended.”

Once I admitted how right he was about my take-charge attitude, I softened and actively sought her opinion. Because her reasoning was now impaired, I didn’t implement all her ideas, but she was happy to be consulted. We both felt more relaxed.

2. Laugh whenever you can.

At the end of that same visit, the boys were settled in the car for our drive to Toronto. When I popped back inside to retrieve something, Mum said to me, “It’s been lovely having you here. Next time bring the boys.” They’d just been living in her house for a week! It took me a couple of weeks to be able to recount her statement to others and laugh about it.

3. Prompt recall with photos.

When mailing a letter or card to friends with Alzheimer’s, I include a couple of photos to remind them who I am. A photo of us together, with date and description of the occasion, brings comfort and prompts recall (which may be fleeting, but gives pleasure). Caregivers tell me these photos are often kept on display.

4. Verify plans repeatedly.

After planning to see each other, I send an email to the caregiver to be sure it’s clear what will happen and when. Then I telephone my friend a couple of hours beforehand to repeat exactly when to expect me and what we’ll do together.

5. Accept superfluous help.

Putting myself in my friend’s shoes, I thank him when he tells me how to drive to our destination. Even though I know the way, he feels knowledgeable and useful when telling me precisely where to turn and where to park. So much of his day involves feeling foggy- brained, clearly recalling a familiar route brings him joy.

6. Stay in the now.

When reconnecting with a fully functioning acquaintance, you likely ask plenty of questions: “Do you remember the time…? How’s your daughter doing? What are your plans for the summer?”

Questions can threaten the person living with the disease because they seldom know the correct answer and worry about getting it wrong. I try to avoid putting them on the spot by using statements. Instead of “How are you doing?” I say, “How lovely to see you again!” When describing a person or place she previously knew well, I over explain – to pre-emptively fill in the details.

When I hear my friend searching for a word, I guess and try to supply it. You need to listen carefully and be completely present to be helpful.

Isn’t that what a social interaction is all about? Nobody knows whether you two will ever see each other again. What matters is your time together today. To keep it smooth and meaningful for your friend, just focus on what will give your loved one the most delight.

The people living with the disease whom I’ve spent time with enjoy talking about concrete, visible things (like a necklace I’m wearing) in lieu of abstract ideas or opinion we would have discussed previously.

If you manage to stay relaxed and flexible as conversation ebbs and flows, chances are they will, too. If you sense that your friend isn’t exactly sure who you are, don’t worry about it. Don’t put them on the spot by asking outright, “Do you remember who I am?” Just drop lots of clues.

Be happy that you are in each other’s company and able to share a goodbye hug before they disappear completely.

Whether you are seeking to support a person with Alzheimer’s or the person that cares for him or her, here are 10 ways you can help a family.

For more information on Alzheimer’s or another dementia visit our website at alz.org

Wise, kind advice, Pat, and beautifully written. Thank you.