Fresno resident uses childhood memories to help mom with dementia

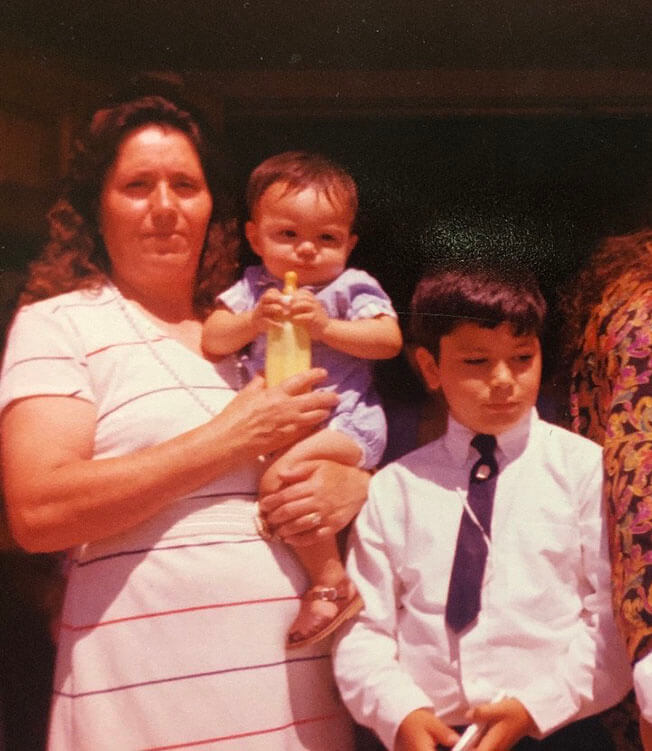

Felipe Cobarruvias and his sister Rosa care for their mother, Maria, who is living with Alzheimer’s disease. Through education and resources provided by the Alzheimer’s Association® and Valley Caregiver Resource Center, Felipe and his family have learned how to provide the best care they can for their mother, including providing her with chickens to care for. Felipe shares some of his favorite tips and hopes that it will help other caregivers.

Feeding her family

Maria Cobarruvias was born in Temastian, Jalisco Mexico where she had five of her 10 children. During the 1970s she and her five children moved to the United States. “She was hardworking and always doing something to make money,” said Felipe Cobarruvias, one of Maria’s sons. “She’d make tamales and sell them around the neighborhood. It got to the point where people were coming to the house to buy them.”

When Maria’s husband left the family in the early 90s, began working a variety of agricultural jobs. Maria made extra money packing lunches for her coworkers, many of which were unmarried men who appreciated a home cooked meal. She also made money selling a variety of other foods like candies, churros and other treats.

“Mom was good at saving money and providing for us,” said Felipe. “Most of her children became college educated and started a career. She knew education was important and pushed that on us. This is what drove all of us to success.”

Normal aging

As Maria aged, she became less independent. Felipe and his sister took on more responsibilities to help care for their mother. However, when Felipe and his siblings noticed that their mom was repeating questions she’d just asked. They assumed that it was a normal part of aging and not a sign of dementia.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association 2022 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures report, 57% of Hispanic Americans believe that a significant loss of memory or cognitive abilities is a normal part of aging. Hispanic Americans are twice as likely as Whites to say they would not see a doctor if experiencing thinking or memory problems.

Finding a doctor

Maria has always been hesitant to see a doctor, part of which had to do with a language barrier as she only speaks Spanish. Whenever Maria had to go to the doctor, one of her children had to be there to translate. Felipe said, “Medical terminology is always an issue and there is never a translator available.”

Luckily, Maria was able to find a local Hispanic doctor that is bilingual and has a strong connection to his patients. “The very first time we met her doctor, he gave us both a hug,” said Felipe. “He made Mom feel very comfortable.”

When Maria’s varicose veins caused an ulcer in her ankle, Felipe called her doctor for help. Maria’s doctor knew that she didn’t like coming to the office and sent over a home nurse to make it easier for Maria to receive the necessary medical attention. The nurse was the one who suggested to Felipe that Maria may need to be assessed for dementia.

“The nurse was the first person to mention that [Mom should] get checked out by her doctor for dementia,” said Felipe. “I thought that maybe mom didn’t understand the questions [the nurse was asking]. The nurse said, ‘Well, I made it pretty simple and she’s still asking the same questions.’”

Making connections

Through Maria’s doctor, Rosa learned about a conference put on by the Alzheimer’s Association, Valley Caregiver Resource Center and UCSF Fresno. The program shares resources, teaches about the disease, and presents strategies on how to better care for your loved one by highlighting current and past caregivers.

“It was like, Wow! This is what is going on in our home,” said Felipe. “We could see ourselves [in the scenarios they were] acting out. The conference was [designed] for us, the children/caregivers, [so we could] see the signs and come up with better strategies moving forward.

“While we were at the conference, we learned about the 10 signs of Alzheimer’s. Mom met eight out of the 10 signs. Now we were sure [she had dementia], we just needed to clarify it. We filled out paperwork, Rosa took her to the appointment and that led to her diagnosis.”

Maria was diagnosed with dementia in 2019.

Sharing the care

Now that their mother had an official diagnosis, Felipe and Rosa knew they’d need even more help. They reached out to their other brothers and sisters to see what support their siblings could provide.

“No one questioned what was going on with mom,” said Felipe. “But there was a lot of work to do, and a lot of it fell on my shoulders. Some of my siblings said they’d help. The biggest concern was making sure mom had food to eat so she doesn’t have to cook. My sister Lorena and brother Mario have increased their role to make sure she eats well daily and is properly cared for.”

Using the tools

Felipe and Rosa have used many different tricks they learned at the conference to navigate the day-to-day care of their mother.

Changing the narrative

Before Felipe and Rosa attended classes, Maria would notice that her purse was missing. She was convinced someone had stolen it. Felipe didn’t know how to address this problem because his mom’s purse wasn’t stolen, she just didn’t remember where she put it. “We would say, ‘Mom your purse is where you always put it, don’t you remember?’”

After taking some classes on dementia, Felipe learned it was best not to ask her if she remembered things. Instead, he would tell her that he put her purse away. It would ease her fears and help her move forward with her day.

Cooking safety

Because Maria spent the bulk of her life cooking for others, she was always in the kitchen. Her dementia has progressed far enough where it was no longer safe for her to cook on her own. “Mom was burning things. She’d put something down and walk away,” said Felipe. “I recalled from the education conference that another Hispanic family had the same situation with their mom. They always had someone bring food over, so she didn’t have to cook, and then they took the knobs off the stove. We have since been doing the same and it has remedied the problem of mom burning food on the stove.”

Changing the environment

When Maria was growing up, it was her responsibility to go out every night, feed the chickens and put them in the chicken coop. Now as an adult, she doesn’t have chickens, but she still thinks she does. “As soon as the sun started going down, she’d go outside looking for her chickens,” said Felipe. “She’d look in the neighbor’s backyard. She’d become very stressed out when she couldn’t find her chickens.”

At first Felipe would remind her she didn’t have chickens but eventually asked himself, “What if I just got her chickens?” During the pandemic, Felipe, who is a middle school teacher, noticed on in one of his virtual classes that one of his students had chickens. He reached out to that child’s parents to learn more and eventually purchase some from them for his mom. Now, his mother happily goes out every night to feed her chickens.

Compassionate communication

Eventually, Maria’s dementia progressed to the point where she doesn’t remember that her parents had died. In the beginning, Felipe would remind his mom that her parents had passed away. “It would ruin her entire day,” said Felipe. “She’d say, ‘I can’t believe you didn’t tell me. Why would you keep this from me?’ It would go on the whole day until she fell asleep.”

After the education classes Felipe took, he decided it was better to let her think her parents were alive, then to tell his mom they weren’t and have her be upset the whole day. “If she thinks her parents are alive, then I reassure her that everything is okay and change the subject,” said Felipe. “I would tell her that they went to the store, or that they’re at their own house and they’ll be here tomorrow. This way we don’t have to have the whole meltdown.”

Advice for caregivers

Felipe knows from experience that many caregivers will see the signs in their loved one but deny it. He recommends that caregivers take classes on dementia to learn as much as you can both about the disease and how to be a better caregiver.

“I was talking with my sister recently,” said Felipe. “She said, ‘Hey I think mom is getting better,’” To which Felipe replied, “No, she’s not getting better, I think we got better on how to utilize those strategies we have learned. Where did we learn that information? Through the Alzheimer’s Association and Valley Caregiver Resource Center.

“So many people are unaware of these free resources. We learned from professionals and those who have previously or are currently going through it. We talked to people who are comfortable talking about [dementia] and who understand. By seeking help, we can make it easier for [people living with the disease].”

Lastly, Felipe wants to remind caregivers that taking care of your loved one living with dementia is a long-term commitment. He encourages caregivers to find time for themselves. “It’s okay to take breaks and lean on the people you can confide in,” said Felipe. “You have to be okay with stepping out for a bit to help yourself too.”

For more information on upcoming education classes visit alz.org/communityresourcefinder or call our 24/7 Helpline at 800.272.3900.

The bilingual caregiver conference Felipe and his family attended returns to Fresno in June. More information will be available at alz.org/norcal/events as the event day gets closer.

Felipe, Rosa and Maria were recently featured on a segment for Fresno’s ABC30. This piece discusses what it’s like to be a sandwich generation caregiver. Someone who cares for both an aging parent and is raising their own children. You can see the segment here.