Navigating dementia care from the other side of the world

In the first installment of this two-part long distance caregiver series, we meet Nita Sharma and her father Mr. Ashoke Sen Gupta who had dementia. Nita lives in the California Bay Area while her father lived in India. Despite a family history of dementia, Nita shares her experience of missing the signs and navigating care not only for her father but supporting her mother in her caregiving journey.

An avid storyteller

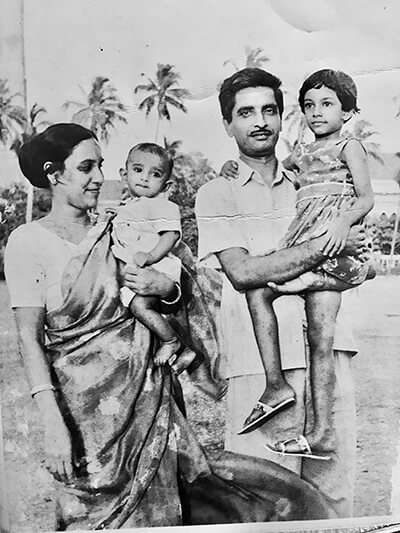

Mr. Ashoke Sen Gupta was a brilliant, creative man who was also an amazing storyteller. Born in what is modern day Bangladesh, he moved to Kolkata, India as a teen and fell in love with the city. He excelled academically, never coming in second and loved to read.

As an adult he never lost his strong imagination, much to the admiration of his children and grandchildren. Mr. Sen Gupta loved the railways and occasionally he’d invite his children on an adventure to “get lost,” spontaneously buying a ticket on the next available train and riding it to the end of the line. On one such trip, he crafted a story so engaging that a stranger on the train missed his stop so he could hear the ending of the tale.

When his grandchildren would visit from the United States, he would make the visit magical. One such time he turned his home into a zoo, hosting various animals such as turtles, birds, rabbits, crabs and of course, a puppy.

Mr. Sen Gupta was known for his amazing memory even into his 70s, remembering things his children, nieces and nephews had long forgotten. “He was a brilliant scholar,” said Nita Sharama, his daughter. “He remembered every article and book he read. He had a penchant for adventure. He went to any length for a loved one, transforming himself to connect with people at their level.”

Missing the signs

India is home to 1.37 billion people and about 8.8 million Indians older than 60 years live with dementia. In the U.S. more than half (56%) of Asian Americans believe that significant loss of memory or cognitive (such as thinking or learning) ability is a normal part of aging. With Mr. Sen Gupta in his 70s, it’s no surprise his family didn’t initially register there might be something wrong. Nita said, “He was in his 70s, I didn’t take it seriously.”

Memory loss that disrupts daily life may be a symptom of Alzheimer’s or other dementia. There are 10 warning signs and symptoms. Here are four that Nita noticed in her father:

- Memory loss that disrupts daily life:

“He started showing signs, when he started forgetting things I would tell him,” said Nita. “I’d tell him anecdotes of my kids’ life and things that were happening. He’d forget those and ask questions over and over again.” - Confusion with time or place:

“Even in his 70s, [my father] used to go for consultations as an engineer in Kolkata to provide advice to the Metro Railway team,” said Nita. “They gave him a chauffeur driven car for transportation. In the evening, the driver called my mother and said [my father was] not to be found in the office or anywhere. A few hours later he turned up home. He took public transportation, forgetting he had a car.” - Misplacing things and losing the ability to retrace steps:

“I gave the keys to my father for the locker where my passport and laptops were stowed,” said Nita. “The night before my trip back to the U.S., I asked my father, ‘I need the keys to open the locker before I leave.’ He had no memory or recollection of him having the key or where he kept it. We had to break open the locker.” - Decreased or poor judgment:

“There was 20,000 rupees ($250 U.S.) missing from his bank account,” said Nita. “That was a large amount at the time. Mother started asking and he had no recollection [of where the money went]. She went to the bank to trace the steps and he had written the check to a temporary maid that came for a few days. She must have influenced him. He’d lost his judgement.”

A history of dementia

In 2014 when Mr. Sen Gupta started having severe headaches, his family brought him in to see a doctor. At first no one could diagnose him. However, after a referral to a neurologist and an MRI, Mr. Sen Gupta was diagnosed with vascular dementia. This is caused by conditions that block or reduce blood flow to various regions of the brain, depriving them of oxygen and nutrients.

Dementia wasn’t new to Nita and her family. Research shows that those who have a parent or sibling living with Alzheimer’s are more likely to develop the disease than those who do not have a first-degree relative with Alzheimer’s. Those who have more than one first-degree relative with Alzheimer’s are at an even higher risk.

“My grandfather didn’t have [dementia] but of his six siblings, three of them had it,” said Nita. “Both of [my father’s] sisters had it in their late 60s. We didn’t expect it [as my father was in his 70s], so for us, it was an issue of denial. But then we realized that we had to get help, accept it and work for it. That was a huge transition for us.”

Oceans and continents-apart care

Both Nita and her bother had moved away from their family home outside of Kolkata. Nita having moved to the California and her brother in Delhi, India (which is roughly 2,300 miles away) which meant that their mother became the sole caregiver for their father. Nita shared, “It was a huge undertaking for my mother.”

Nita and her brother, partially driven by guilt at not being there physically to help, did everything in their power to set their mother up for success. They reached out to family for support, set up local doctors and therapist to come to the house, organized caregiver support when the time came and helped take care of the legal and financial planning that needed to be done*.

Additionally, Nita set up a CC TV system in the house to watch and communicate with her parents from her own home. “I could monitor and see things,” said Nita. “In India, caregivers are not always of quality. I had to make sure everything was fine.”

Mrs. Sen Gupta’s health declined

For some caregivers, the demands of caregiving may cause declines in their own health. Evidence suggests that the stress of providing dementia care increases caregivers’ susceptibility to disease and health complications. Seventy-four percent of caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s or other dementias reported that they were “somewhat concerned” to “very concerned” about maintaining their own health since becoming a caregiver.

Data from a Health and Retirement Study showed that dementia caregivers who provided care to spouses were much more likely (41% increased odds) than other spousal caregivers of similar age to become increasingly frail during the time between becoming a caregiver and their spouse’s death.

This was true for Mrs. Sen Gupta who had a medical emergency while caring for her husband and collapsed. Because Nita and her brother had not thought something like this would happen, there was no plan in place on what to do. Luckily a kind housemaid spent her own money to get Mrs. Sen Gupta to the hospital and told them it was her mother.

“That was when we realized we had to be prepared for emergencies,” said Nita. “We connected with ambulance providers. I made sure there was a 24/7 ambulance. We set up a neighborhood support system that included young men. We made sure that our mother would get the right support in case of an emergency.”

From there Nita and her bother hired extra caregivers, and backup caregivers for around the clock care effectively removing the burden from their mother. “Mother is a natural caregiver, she loves caregiving,” said Nita. “We built a support system where she just had to monitor [our father] not physically do anything. We had to set up support for her wellbeing as well.”

Giving back to the Association

Nita continued to remotely care for her father either through phone/video calls or by visiting a few times a year. Due to travel restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, she was sadly unable to be with him when he died in 2021.

While her father was alive, Nita used the Alzheimer’s Association’s website as a way of finding information on the disease to better help her father. After his death, she wanted to find a way to give back to the organization. Since then, Nita has participated in Walk to End Alzheimer’s, A Bright Night gala and is currently a volunteer. Starting in February, Nita will be leading a support group for others who are caring for a loved one in another country.

Additionally, Nita has written a book, “Hold My Hand as the Memory Fades” about her experiences where she reminds us that “In the song of silence, love needs no words, and connection lives beyond sound.”

*For more information about Nita’s experience with long distance caregiving including tips, tricks and how a support group might help you, come back next week for the second installment of our two-part long-distance caregiving series.

For more information on how to join the new support group, Caregivers Across Borders, call our 24/7 Helpline at 800/272/3900.

To learn more about Alzheimer’s in the Asian American community visit alz.org/asianamericans.